Defining The Disruptive Geopolitics Of The Global Farms Race

February 17th, 2015

Via Harper’s, a slightly dated (2014) but interesting article on an Ethiopian billionaire’s outrageous land grab:

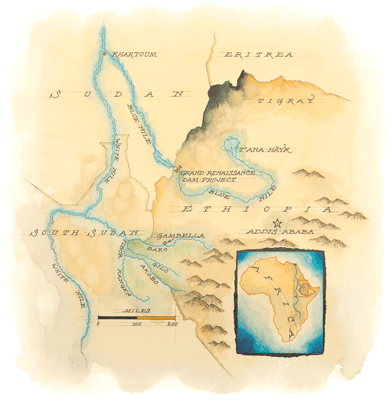

Forget about diamond heists, bank robberies, and drilling into the golden intestines of Fort Knox. In this precarious world-historic moment, food has become the most valuable asset of them all — and a billionaire from Ethiopia named Mohammed Hussein Al Amoudi is getting his hands on as much of it as possible, flying it over the heads of his starving countrymen, and selling the treasure to Saudi Arabia. Last year, Al Amoudi, whom most Ethiopians call the Sheikh, exported a million tons of rice, about seventy pounds for every Saudi citizen. The scene of the great grain robbery was Gambella, a bog the size of Belgium in Ethiopia’s southwest whose rivers feed the Nile.

I wanted to get to Gambella to see the Sheikh’s plan in action. A friend of mine at the State Department suggested I contact a fixer she knew once I got to Addis Ababa. When I met Aman on my second morning there, he looked the part — blue jeans, black button-down, pin-striped jacket, dark glasses. (He asked that I not use his real name for fear of retaliation by Al Amoudi.) The backstory was good, too: Aman had been raised a devout Muslim but had grown out of religion. Now he was a writer, an editor, and an entrepreneur; his résumé included a year at an English-language business weekly, where he had been schooled in the ways of Ethiopian banking, manufacturing, and real estate. Plus, he knew Fikru Desalegn.

Fikru, explained Aman, ran the Sheikh’s rice operation in Gambella, otherwise known as Saudi Star farm. Fikru could get us onto the farm. Where, I asked, could we find Fikru?

“He’s in town,” said Aman.

We were speeding past Meskel Square in his black subcompact, cutting between the mule carts, charcoal sellers, and groups of beggars. I figured we were heading straight to Fikru’s office for an interview, but Aman pulled into the muddy parking lot of Ethiopia’s Ministry of Agriculture, a six-story concrete relic of the country’s sixteen years of communist rule, which ended in 1991.

We walked up the ministry’s marble stairs to the fourth floor, home of the Agricultural Investment Support Directorate. Aman had made an appointment to discuss Sheikh Al Amoudi with the bureau’s director, Esayas Kebede, but after announcing our presence in Amharic he reported back in English that unfortunately Esayas Kebede was in a meeting somewhere else.

As we waited, I read a pamphlet, Ethiopia: The Gifted Land of Agricultural Investment.The government owns all the land in Ethiopia. They cannot sell it, but they can lease as much of it as they want. By leasing to the Sheikh, the directorate had given Al Amoudi’s food grab the federal stamp of approval. Though the terms of the deal have never been released, the annual price per hectare has been estimated at no more than seven dollars. In Zambia, by comparison, the average hectare leases for about $1,250 a year.

The sun was low in the sky when Esayas arrived, and without looking up from his BlackBerry he led us into a small conference room. I wanted to ask him why the bureau had given the Sheikh preferential treatment, figuring he would reveal a few things I could use when I talked to Fikru. But before I could begin, Esayas launched into a speech. Agriculture accounted for 42 percent of Ethiopia’s GDP, he said. More than four out of five people work the land, and Ethiopia’s Growth and Transformation Plan, introduced in 2009, had laid out a five-year strategy for the country’s farmers.

I asked whether the politicians behind this plan considered it unusual that Ethiopia, where 30 million of 90 million people are undernourished, would soon feed Saudi Arabia, where there was no particular lack of food.

“Ethiopia’s land can feed all the African people,” said Esayas, “and more than that.”

Since becoming director, Esayas had done a fair bit of public speaking, which had taken him from Beijing to New Delhi to Hyderabad. He was not about to go off script. “Investment is a win-win,” he said. “Our job is to change Ethiopia from an aid destination to an investment destination.”

But how could Ethiopia feed the world if Ethiopia could not feed itself?

“The core point,” said Esayas, “is water development.”

Of all the stories and subterfuges, this was the most hackneyed. I didn’t care about Nile water and its source. I wasn’t interested in Henry Morton Stanley, David Livingstone, John Hanning Speke, or any of the other dead Victorian explorers, no matter how many specials PBS and the BBC made about them. On TV, in print, online — every story was a water story, but I was not about to turn my attention away from the Sheikh’s rice.

Esayas was looking at his BlackBerry.

I asked how he could allow Ethiopia to prostitute its food supply.

Esayas stood up, headed out the door of the conference room — then stopped, turned around, and gave me a bit of advice. “Write what you see,” he said. “Don’t write what you feel.”

It was dark by the time we were done with Esayas. Aman drove through a slum toward a shining castle atop a hill, the home of African Union summits and Microsoft press conferences. This was the Sheraton Addis, owned by Al Amoudi and built on the site of a bulldozed shantytown. After construction was completed, the Sheikh laid waste another 3,000 homes to expand the hotel and improve the view from the pool.

I asked whether we would see Fikru at the hotel.

“Maybe,” said Aman.

“Do we have an appointment with Fikru?”

“Tomorrow.”

Guards armed with AK-47s waved us through the wrought-iron front gates into a world of delight: flowers, fountains, palm trees, mowed lawns, street lamps, and British-style red telephone boxes. In front of the entrance was a statue of a horse rearing up on his hind legs, so the weary traveler could gaze upon his silver penis. Staff in top hats and tails stood at attention under the arches of a grand arcade. But the effect was marred a few yards beyond the glittering vaults and cupolas, where we found three airport scanners — two for people, the other for luggage. One of Cinderella’s coachmen gave me a thorough frisk.

Aman had assured me that the Sheraton would be worth our while, that with a little luck we would run into some Saudi Star executives just in from the rice farm. So we walked down a golden hallway to Stanley’s, a bar of the dark-wood-and-brass variety, hung with sepia images of African princes, African explorers, and the cataracts of the Nile.

Aman stopped to pay his respects to two men. While he spoke to them I settled onto a stool at the opposite end of the bar and tried to decide among twenty-two varieties of vodka and thirty-one kinds of scotch. I considered a croque monsieur and Buffalo wings along with a glass of 1925 Armagnac, but settled instead on a couple of locally brewed St. George beers.

When Aman sat down he explained that one of the men owned a number of buildings in downtown Addis and the other was a politician from the northern region of Tigray, home base of the ethnic group that has ruled Ethiopia since the country’s 1991 coup. Aman told me the politician was known around Addis as Money Man.

A couple of rounds later there were still only the four of us at Stanley’s, so we stood and headed for the door. On our way out, Aman introduced me. Money Man had bloodshot eyes and a nasty scar on his forehead. He shook my hand and asked what I was doing in Addis. I told him I was a reporter.

What was I reporting?

I said I planned to visit Gambella and report on Saudi Star farm.

“Inform the public correctly,” he said.

“Of course,” I said.

He took a sip of red wine and stared at me. I supposed he could deliver me to the Sheikh’s farm with a wave of his pudgy, gold-ringed finger — but first he would have to let go of my hand, which he would not do.

He studied my face, then turned to Aman, grabbed his beard, pulled him close, and whispered in his ear.

When we got back to the car, Aman sat for a while with the lights off.

“You’re scared,” I said.

He turned the ignition. “Of course.”

The next morning, over a breakfast of cappuccino and chechebsa — strips of fried bread sprinkled with berbere, a spice mixture containing red chili, garlic, and an herbal laxative known locally as korarima — Aman wanted to talk about gold. He told me that the Sheikh had his hands on a mine 300 miles south of Addis that produced just under five tons of ore every year. He refined this in Switzerland, then sold the bars to Germany’s Commerzbank.

Al Amoudi was then the world’s sixty-first-richest man, with assets of more than $12 billion. And now, Aman said, his geologists had discovered gold deposits elsewhere in Ethiopia that would yield an additional ten tons a year for the next half century. The new trove would raise the Sheikh’s fortune by $4 billion.

“I thought the Sheikh was interested in food,” I said.

Aman just stared at me.

We sat in silence and chewed our chechebsa. Whether or not there was reason to fear the Sheikh and his thugs, Aman clearly did not want to visit Gambella, where there was nothing but heat, humidity, tractors, and experimental paddies of basmati rice. And then there was Money Man, who might have muttered to Aman that I should be dissuaded from poking around Saudi Star farm. Gold had diverted many a past explorer. Why not this one?

After breakfast we headed downtown toward the MIDROC building, headquarters of the Sheikh’s Ethiopian enterprises. Mohammed Al Amoudi founded the Mohammed International Development Research and Organization Companies in 1994, and although the firm had a great deal invested in food, it also manufactured nails, fluid packs for IVs, and much more. One MIDROC subsidiary produced 29 million corrugated boxes a year. MIDROC’s detergent plant spewed forth eight tons of laundry soap each hour. The Sheikh had a leather business, a particle-board business, a dairy business, a supermarket chain, and a cement factory — all of this in addition to his airline and travel agency, his Pepsi bottling plants and Chevrolet dealerships, and, of course, MIDROC Gold.

I assumed that Fikru and the offices for Saudi Star farm were in the MIDROC building, but Aman drove by without stopping. The farm’s corporate headquarters had yet to move into the Sheikh’s skyscraper, he said.

Fifteen minutes later he parked in a puddle of mud and we made our way through a herd of sheep. The road — or, more accurately, the busted rock and bits of broken pavement — was dotted with their crap.

“My city,” said Aman, “which I don’t like anymore.”

We entered the gray concrete six-story premises of Saudi Star farm, a clone of the Ministry of Agriculture: Soviet construction, circa 1984. The waiting room featured stained carpets, twisted blinds, exposed wiring, a dying houseplant, and flickering fluorescent lights. Aman checked his Samsung, then broke the news. Unfortunately, Fikru Desalegn would not be available for an interview.

Nor would his second-in-command.

However, Aman said, there was a midlevel manager who happened to be in the building, a civil engineer involved in operations. He had ten minutes for us in the conference room next door, and his name was Yitagas.

Yitagas turned out to be a humorless young man with a nothing-but-the-facts manner: The farm employed five site managers. The farm had brought in 410 farm machines. The farm was constructing a geomembrane.

What, I asked, was a geomembrane?

Yitagas gave me a look. “The core point,” he said, “is water development.”

Clearly, Yitagas had been given the same script as Esayas, which I imagined had been written by Fikru, perhaps under the supervision of the Sheikh. Unfortunately, there was no room for improvisation. So I told Yitagas that yes, I had come to his country to witness the water development.

I had yet to become accustomed to the protracted silences that punctuate Ethiopian conversation, so when Yitagas leaned back in his chair to check his handheld I assumed our meeting had come to an end. I closed my notebook and stood, at which point Yitagas looked up from his screen and said that he was flying to Gambella the next day and there might still be a few tickets available. If there were, he would be happy to put us up at Saudi Star farm.

Aman sat poker-faced.

“That’s too kind,” I said.

The Sheikh’s rice theft could only have been possible in a part of the world no one identifies with rice.

When Alexander the Great came to Luxor he did not ask about the meager harvests that had led to the downfall of the empire of the pharaohs, nor did he inquire about the sphinxes, the murals, or the colonnades. He asked instead about the source of the Nile, and why it rose every summer. Four hundred years later, the Romans sent two centurions to discover the answer to the water question — which they never did.

Meles Zenawi, prime minister of Ethiopia from 1995 until his death, in 2012, knew where the Nile came from. He knew the secret of the river’s annual rise, knew why life came to the desert in the hottest months of the year. The 5,000-year-old mystery turned out to have a simple answer: The rainy season in Ethiopia begins in June and ends in September, and more than four fifths of the Nile’s water comes from the country.

Zenawi understood that the Horn of Africa could be mastered by controlling the deluge that crashed down from his country’s highland plateau. Hydro-hegemony could even mean a return of Aksum, an Ethiopian kingdom that overran Arabia, pushing up against the empires of China and Europe — in the first millennium a.d.

And so Zenawi spent a great deal of his political career planning and financing and constructing dams to manage the flow of water from Ethiopia to Eritrea, from Ethiopia to Djibouti, from Ethiopia to Kenya, and from Ethiopia to Somalia. He knew that 77 percent of East African city dwellers had no access to electricity; Ethiopia’s rivers could light a swath of earth two thirds the size of Europe. Ethiopia would share the global energy stage with the United States, Russia, China, and the Arab states. And whenever Ethiopia wanted, it could turn off the lights.

Zenawi’s dream could also settle old scores. First among resentments: Egypt, a country that has the right to use three quarters of the Nile’s water but contributes nothing to the flow. Of all the water developments envisioned by Zenawi, the greatest was Project X, a dam that would impound the Blue Nile.

The proposed Project X dam flouted a compact that dated to 1959 whereby Egypt and Sudan were granted the rights to Nile water — with none for anyone else. Not surprisingly, neither Egypt nor Sudan would invest in the $4.7 billion scheme.

“Unfortunately,” Zenawi said in April 2011, “the necessary climate for engagement, based on equitable and constructive self-interest, does not exist at the moment.” He then announced that his country would fund Project X on its own, and that Project X would no longer be known as Project X but as the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

Of course, Zenawi would fail, as all the other Nile fools had failed. Egypt would never let him stop the flow; Zenawi’s speech was merely political grandstanding. And a little more than a year later, he contracted a mysterious illness and died. Among the Chinese, Indian, and U.S. dignitaries, the African presidents, and the Ethiopian Orthodox clergymen who attended the funeral in Addis Ababa, Sheikh Mohammed Hussein Al Amoudi held a place of honor.

Aman and I arrived at the airport at nine a.m., three hours before the flight to Gambella. Our punctuality turned out to be wise, as the line outside the airport stretched into the parking lot. But beyond the security checkpoint the airport turned out to be deserted, and as far as I could tell the only departure that day was our twin prop to the swamp.

The gate was a merry spot, a mini-reunion for Yitagas, Saudi Star execs, and the dozen or so Nuer men who were heading home.1

1 The Nuer are the largest ethnic group in Gambella, though most still live in South Sudan. Tens of thousands crossed the Baro River into Gambella at the height of the Second Sudanese Civil War and eventually claimed Ethiopian citizenship.Aman and I nodded hello to Yitagas, then Aman introduced me to a former editor of the weekly newspaper where he used to work. I was curious to know what story the editor was covering in Gambella, but it turned out he no longer worked as a journalist. He was now employed by a British risk-management company that helped businesses operate in complex and hostile environments. I was about to ask what clients the company had in Gambella, but the time had come to board.

The city of Addis Ababa stands at an altitude of about 8,000 feet, so it felt like most of our flight was spent descending. After an hour in the air I could see the Baro snaking its way through the fen, the largest waterway amid a thicket of streams and courses that hydrologists call the Baro-Akobo River Basin. The fluvial lacework eventually forms a border with South Sudan, where the Ethiopian tributaries congregate and become the Sobat — which a few hundred miles downstream feeds a section of the White Nile known as the Bahr al Jabal, or River of the Mountain.

We touched down not far from Gambella town, the capital of the region. An airfield had been hacked out of the forest, and ranks of Sudan grass grew thick alongside the tarmac. It was now late afternoon, but heat still penetrated the corrugated-metal shack where our bags had been dropped on a slab of poured concrete. The dirt around the airport shack was crowded with black four-by-fours and white pickups stenciled with the initials and insignia of the International Organization for Migration, the World Food Programme, the Red Cross, and various branches of the United Nations, most prominent among them the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees.2

2 The United Nations keeps busy in Gambella, where members of the Anuak, Komo, Majangir, Nuer, and Opo ethnic groups contend for land and resources. There are also highland immigrants from the Ethiopian regions of Amhara, Tigray, and Oromia, 50,000 refugees from South Sudan, and a miscellany of asylum seekers from Uganda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.Aman introduced me to the driver he had conscripted to take us to the farm. Teddy wore shorts and Pumas and drove a gold Nissan Patrol. He had strapped two spare tires and three twenty-seven-liter containers of gasoline to the roof; filling stations were scarce in the region.

We stopped beside Yitagas and waited for four jeeps full of soldiers, who would join us on our journey. They pulled in front of us, aimed their rifles at the jungle on either side of the road, and then our convoy roared off past the twisted trees and cell phone towers.

“You can’t believe how green this place is,” said Aman. “It’s like Iowa.” He had once been to Des Moines, on a reporting tour for a pan-African news agency.

After an hour or so on the empty dirt road, we had managed to rumble about twenty miles south of the airport. We began to pass men with machetes on their waists and pickaxes on their shoulders, some carrying huge bundles of sticks on their heads, others lugging water. After another mile we arrived at a village called Abobo, where we saw a few stalls with bags of rice for sale. We would have driven by without stopping, but a herd of goats had congregated in the middle of the road. As our little convoy came to a halt, the people gathered round. The villagers were Anuak, members of the second-largest ethnic group in Gambella.

Recently, the Anuak had attracted the attention of Genocide Watch, which characterized the Ethiopian government’s approach to the group as a “campaign of genocidal violence” that had forced between 6,000 and 8,000 people to flee Ethiopia for the relative safety of Sudan. Six months before I arrived in Ethiopia, unidentified gunmen opened fire on a Gambella town bus and killed nineteen people. A month later, another group of unidentified gunmen invaded the Sheikh’s rice farm and killed two Pakistanis and three Ethiopians. The government suspected that Anuak employees of Saudi Star had been complicit in the raid, so the next day soldiers arrived and killed four of them. According to Human Rights Watch, federal troops then descended on the neighboring Anuak villages and searched the houses, arrested the men, and raped the women.

After the goatherds had cleared the road the soldiers relaxed and Teddy followed Yitagas and his caravan west toward the border with South Sudan. An hour later we came to a barbed-wire fence, then passed a sign in Amharic and English, barely visible among the jungle vines, for Saudi Star farm. We drove another half hour before we passed our first vehicle traveling in the opposite direction, a pickup packed with day laborers. Soon after that we arrived at a checkpoint, where two guards pointed their rifles at us — then recognized Yitagas. They unlocked the gate and as dusk fell we pulled into the central compound of Saudi Star farm.

“Hallelujah,” said Aman.

Saudi Star’s headquarters looked like it belonged to a Bond villain, a tractor-flattened landscape filled with klieg lights, satellite dishes, and rows of white barracks. Men in robes and long beards wandered about — Pakistani rice technicians.

“Who built all this?” I asked.

“A contractor from Dubai,” said Yitagas.

What contractor?

“A brother of the Sheikh,” said Yitagas.

He led the way to the biggest barracks, a double-wide trailer with an air-conditioned conference room. Someone had taped a schematic of the farm to one wall. An engineer began to explain the intricacies of a 10,000-hectare tract that had been divided and subdivided into sectors and subsectors, each labeled with a name such as BC2/DY6-6/IL.

By the time the explanation was over more than twenty Ethiopians had arrayed themselves around a plastic table. Yitagas settled himself at the head and indicated that Aman and I should sit opposite him. He started the meeting on a grand note.

“Welcome to where the wind starts,” he said.

As if on cue lightning flashed outside the window, illuminating the red smoke of the jungle, which was being cleared by fire. The night crews were out, bulldozing more of the Sheikh’s land.

Yitagas sipped a glass of mango juice. “Have a beer,” he said, and the room of Ethiopians watched in silence as a young girl in sandals produced two St. Georges and set them in front of Aman and me. I worried that Yitagas had grown suspicious — most likely after consultation with the elusive Fikru. Now that I was here, he saw the risk I could pose. So, like Aman, he tried to turn my attention away from the rice. Yitagas noted that only a hundred kilometers from where we sat we could observe native Gambellans living in picturesque villages, undisturbed by modernity. Why not head over there in the morning? Why, Yitagas continued, wouldn’t I contemplate a visit to the smoking waters of Blue Nile Falls, where millions of gallons cascade over cliffs and circular rainbows adorn the skies for tourists to enjoy?

I said I liked Gambella.

“Why do you like Gambella?” asked Yitagas. “Because it is hot?”

The Ethiopians thought this was a fabulous joke. I knocked back the rest of the St. George, told Yitagas we would see him in the morning, and walked out.

Aman and I had been told to eat dinner with the Pakistanis, so we hurried over to their barracks and joined them around a flatscreen television that piped in the news from Peshawar. The rice, pumpkin, lentils, chapati, and pineapple pudding were surprisingly good.

As we lingered over glasses of mint tea I learned that while Saudi Star’s first rice harvest had been plentiful, the plants had reached maturity just as flocks of migratory birds swooped across the Horn of Africa. The birds had eaten nine tenths of the Sheikh’s crop; the team had had to start over. The debacle was discussed openly as a failure, for it was easily remedied: rice can grow almost any month of the year in Gambella. Next time the rice would be ready when the birds were flying over some other country.

After dinner I retired to my one-room trailer, where I found the plasti-wood floor was warped, mud-stained, and inhabited by throngs of fat black beetles. When I lay down on my cot the bugs crawled into bed with me.

To everyone’s surprise, in April 2011, the Ethiopian government began excavating the site for the Grand Renaissance Dam and poured the first phases of the concrete structure. Two years later, Ethiopia diverted the Blue Nile 600 yards from its natural course and Egyptian president Mohammed Morsi convened a secret meeting in Cairo. Unfortunately, someone forgot to turn off the television feed, so Morsi’s conclave was broadcast live throughout Egypt.

As all of Cairo watched in disbelief, Egypt’s political elite sat around a conference table and pondered their options. Younis Makhyoun, leader of an ultraconservative Islamist party, suggested that Egypt back rebel groups in Ethiopia. “We can communicate with them and use them as a bargaining chip against the Ethiopian government,” he said. “If this fails, then there is no choice but to use intelligence to destroy the dam.”

Ayman Nour, head of the liberal El Ghad party, proposed that Egypt spread a rumor that its military was about to purchase refueling aircraft — thereby creating the impression that Egypt was planning an air strike to destroy the dam. “This could yield results on the diplomatic track,” noted Nour.

Magdy Hussein, another Islamist politician, disagreed. Hussein warned that talk of military action would only turn the Ethiopians into Egypt’s enemies. Open conflict was a bad idea; Hussein suggested organizing a film festival in Addis instead.

Afterward, President Morsi made a public declaration: “We cannot let even one drop of Nile water be affected,” he said. “If it diminishes by one drop, then our blood is the alternative.” Daily News Egypt reported that some Egyptian politicians considered Morsi’s statement “a declaration of war.”

One Sudanese secession and one (more) Egyptian coup d’état later, threats and counterthreats over the dam continued. “We will not negotiate on this issue,” the head of Ethiopia’s Boundary and Transboundary Rivers Affairs Directorate declared earlier this year, to which Egypt’s Irrigation Minister retaliated, “We have exhausted all opportunities to negotiate with Ethiopia.”

When the sun rose I opened the trailer door to gusts of swamp air laced with the stink of diesel and pesticide. The orange night sky had turned to white haze as the burning of Gambella continued. Row after row of metal prefab sheds shimmered beneath the sun, along with dozens of black Toyota pickups, acres of bare dirt, and miles of barbed wire. Anuak day laborers were already lugging barrels of fuel and water around camp and picking through a low mound of what was left of the pilot-study rice. At last I could investigate the Sheikh’s land grab at the scene of the crime.

Yitagas met us after breakfast and introduced me to a heavyset project manager named Deribew Shanko who wore khakis and a pink shirt — an Ethiopian preppy with a walkie-talkie and a brother who drove a cab in Washington, D.C. We packed into Teddy’s four-by-four and followed a dirt road that soon narrowed to a single lane between screens of jungle grass. I listened as Deribew laid out the details of an extraordinarily complex irrigation system, but eventually stopped taking notes on flow divisions and field turnouts. I stared out the window at the yellow-billed marabou storks that scanned the tractored fields for carrion.

“The birds are big,” said Deribew. “They can swallow the head of a sheep.”

Why, I asked, were there so few trees?

“They must all be destroyed,” said Deribew. “They are home for birds.”

We stopped near a ditch where men in hard hats were constructing a trough of reinforced concrete. Deribew explained that this would become a storm drain, there to protect the irrigation system from flash floods, a way to keep the water from the water.

I noted that there was already a good deal of water at the bottom of the ditch.

“This is not from our dam,” said Deribew. “That is from God.”

A little while later we pulled up to an enormous cement mixer. Because of the heat the barrel had to be wrapped in muslin and continually soaked by a hose from a water truck. We got out of the car and watched the aggregate from the mixer stream through a black rubber tube that spewed the cement up the walls of a plastic lining that had been stapled to the sides of the ditch. This was the geomembrane, which had arrived from Dubai in one-millimeter-thick sheets. It stretched to the horizon in both directions.

The lining would ensure that no water would seep from Saudi Star’s canals back into the red earth of Gambella. Any water that entered the system would either evaporate or wind up in a desert more than a thousand miles to the northeast — embedded in the grains of rice.

Deribew introduced me to the geomembrane engineer, a mud-caked Pakistani who motioned to me surreptitiously as soon as Deribew turned around. Sweat poured down his face as he gazed across the wet concrete to the jungle, where spear grass shot up ten feet.

“It is dangerous here,” he told me.

I did not know whether he was referring to the rapes and murders reported by Genocide Watch or something new.

“People have been killed,” he said.

“Can you tell me,” I began — but Deribew had returned to my side.

“Not many Americans around here,” I said to no one in particular.

“They are not hard workers,” said Deribew, and he laughed.

We walked over to one of the pilot rice paddies.

“How much water does that take?” I asked.

“Like a pond,” said Deribew. “It soaks for three or four days. Then they drill the seed, then they fill the field again with water.”

I asked, “Is there a crop that uses more water than rice?”

“Not to my knowledge,” said Deribew.

“Isn’t it ironic that rice uses more water — but is most popular in the desert?” asked Aman.

Deribew said nothing.

Which was when I realized that my food story had become a water story after all. The Grand Renaissance Dam was a distraction: even if Ethiopia managed to build it, the dam would not change the flow of water to Egypt. But, grain by grain, the rice from Saudi Star farm would. The Sheikh had solved the fatal riddle. The policy he and his cronies proudly trumpeted — water development — would allow him to acquire what Meles Zenawi only dreamed of having: the Nile.

The hydrological consequences would be astounding. Each acre of rice requires a million gallons of water a season, which means the Sheikh’s project could eventually suck more than a trillion gallons from the Nile. From November to February, the farm would extract more than 10 percent of the White Nile’s total flow. In a dry year, even more.

Saudi Star farm was a different story from the one I had come to report, and for the first time since I arrived in Ethiopia, I was more nervous than Aman.

“When’s the next flight to Addis?” I asked.

On the way back to Gambella town, Aman said a few words in Amharic and Teddy pulled up alongside a river that stretched a quarter mile wide. This was the Baro. We got out of the car and hiked to a grove of mango trees, where Anuak and Nuer men sat together in the shade, along with refugees from the north and nomads from the west and transients from who knew where. Those who were not sleeping chatted over glasses of peanut-butter tea and chewed khat.

Ethiopia is the khat capital of the world, and the business is worth hundreds of millions of dollars. It’s also one of the few Ethiopian commodities Mohammed Al Amoudi does not control. Chewing the oily green leaves is known to induce mild euphoria and can soothe the nerves. Aman bought a bundle and distributed it among us.

On either side of the river, seeds sprouted from the dark silt — just as they had for thousands of years from Luxor to Giza. “They never irrigated,” said Aman, whose tongue had turned green. “They watched the water pass by.” Then he told me that the Amharic name for the Nile was Abai, which means “betrayal.”

At the airport we found the same group going back to Addis that we had encountered heading out to Gambella, including the ex-editor now employed by the British risk-management group. He asked why I had come to Gambella, so I told him my plan to write about Mohammed Al Amoudi.

“He is a thief,” he said.

“I take it you are off the record.”

“On the record,” he said. “The Sheikh — he owes two hundred eighty-five million dollars. Debt he didn’t pay. He borrowed two hundred sixty-three million from the government to pay for the Sheraton. That was the total cost, by the way. Now I work this bullshit for the British.”

“Who’s the client in Gambella?” I asked.

“The company doesn’t allow me to know who the client is,” he said. “But I know.”

“Are you working for the Sheikh?” I asked. He pulled me away from the crowd and held my shoulders. His one good eye spun from one corner of the hangar to the other. “Feel my heart,” he said, and pushed my palm to his chest. Then he began to shout in my face. “If they want to kill me, I’m ready! They can come and get me! It is better than dying by silence!”

The doors to the tarmac swung open to the roar of the twin prop.

“The Sheikh is a tool!” he shouted.

I walked away, but he followed me across the runway, and although I could not hear him I knew he was repeating the rumors — that the Sheikh was a stooge for the Saudi royal family; that he was a whiskey-drinking marauder whose thugs trolled the Sheraton for women; and, most damaging of all, that the Sheikh financed Al Qaeda. Al Amoudi’s lawyers had sued Elias Kifle, editor of the Ethiopian Review, for libel over that story and won.

I no longer cared about the gossip, and when the man insisted I sit next to him on the plane it was with reluctance that I complied. For the next hour he filled my ears with scandal. A few months later, he asked that I remove his name from this article.

In Ethiopia, all things bright and shady start and end at the Sheraton. My last night in Addis, Aman and I made it back to the hotel and headed over to the pool, where the bar was packed. I bought a beer and watched the whiskey-drinking marauders. Aman tapped my shoulder and smiled. “Look,” he said. I followed his gaze to a compact man in a dark suit who sat on a bar stool surrounded by three or four much larger men.

“It’s Fikru.”

Aman insisted I say hello, so he brought me over and I shook hands with the Saudi Star CEO. I thanked him for extending the hospitality of his crew in Gambella. I mentioned the professionalism of Yitagas and Deribew. Then I explained how I had been wanting to interview him since I had landed in Ethiopia, but had just thrown away my list of questions.

Fikru nodded and said nothing. I wasn’t sure he had even heard me. His eyes strayed over my shoulder to the people by the pool. I turned and saw Ivy League Africanists, European aid workers, politicians, prostitutes, gunrunners, helicopter pilots, diplomats from South Sudan, and careerists from the WFP, UNHCR, and USAID — all of them well-fed, drunk, and dancing close to the water’s edge.

This entry was posted on Tuesday, February 17th, 2015 at 1:14 pm and is filed under Uncategorized. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Educated at Yale University (Bachelor of Arts - History) and Harvard (Master in Public Policy - International Development), Monty Simus has long held a keen interest in natural resource policy and the geopolitical implications of anticipated stresses in the areas of freshwater scarcity, biodiversity reserves & parks, and farm land. Monty has lived, worked, and traveled in more than forty countries spanning Africa, China, western Europe, the Middle East, South America, and Southeast & Central Asia, and his personal interests comprise economic development, policy, investment, technology, natural resources, and the environment, with a particular focus on globalization’s impact upon these subject areas. Monty writes about freshwater scarcity issues at www.waterpolitics.com and frontier investment markets at www.wildcatsandblacksheep.com.