Defining The Disruptive Geopolitics Of The Global Farms Race

July 17th, 2022

Courtesy of The Financial Times, a look at the imminent rise of scuffles between local populations and new global landlords:

Donald Trump stole headlines as US president when he was reported to be interested in buying Greenland. The self-governing Danish territory rebuffed the idea and declared itself not for sale. But transnational land deals are hardly an anomaly.

Food insecurity is accelerating the practice. Turkey is among those seeking pastures new in order to feed its population. As inflation soars, the country hopes to revive a flagging deal for a 99-year lease on 800,000 hectares in Sudan.

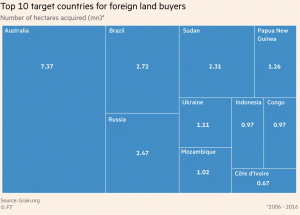

Nearly 500 such deals took place in the decade to 2016 according to Grain, an NGO tracking farmland leases which uses data from the project farmlandgrab.org. These deals covered more than 30mn hectares of land in 78 countries, many in Africa. That adds to pressure on depleting resources such as water. But the dash for food, exacerbated by refugee crises, climate change and war, suggests more activity to come.

Private companies have joined the land grab. In 2008 South Korea’s Daewoo Logistics snaffled a 99-year lease on 1.3mn hectares — half the size of Belgium — in Madagascar. Proposed price tag: zero. “We want to plant corn there to ensure our food security,” a manager told the FT at the time. “Food can be a weapon in this world.”

The backlash that the deal triggered, not least because it played a part in unseating President Marc Ravalomanana, shrank several future plans. Others, including in Latin America, have been restructured into more palatable formats, such as those based on securing farms’ output rather than the land itself.

But controversial deals are still going ahead. The Abu Dhabi-based Elite Agro, a big landowner in Serbia, has signed a deal for farmland in Madagascar. US-based African Agriculture (AAGR) has big plans for growing alfalfa in Senegal and late last year inked agreements for land in Niger.

The group, which is controlled by Romanian-Australian mining tycoon Frank Timis, filed to list on Nasdaq at the end of June. AAGR says that it has provided schools and food in Senegal, and is seen as a force for good. But some communities in Senegal are pushing back, saying the land belongs to them. They are demanding that it be returned.

There will be plenty more scuffles between local populations and new global landlords. But such fights are unlikely to stem the tide of land investment.

This entry was posted on Sunday, July 17th, 2022 at 7:44 am and is filed under Uncategorized. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.

Educated at Yale University (Bachelor of Arts - History) and Harvard (Master in Public Policy - International Development), Monty Simus has long held a keen interest in natural resource policy and the geopolitical implications of anticipated stresses in the areas of freshwater scarcity, biodiversity reserves & parks, and farm land. Monty has lived, worked, and traveled in more than forty countries spanning Africa, China, western Europe, the Middle East, South America, and Southeast & Central Asia, and his personal interests comprise economic development, policy, investment, technology, natural resources, and the environment, with a particular focus on globalization’s impact upon these subject areas. Monty writes about freshwater scarcity issues at www.waterpolitics.com and frontier investment markets at www.wildcatsandblacksheep.com.